The Internet Archive attacks: A crime against humanity

Throughout October, archive.org has been the target of numerous DoS attacks, and the data of roughly 31 million users has been exposed.

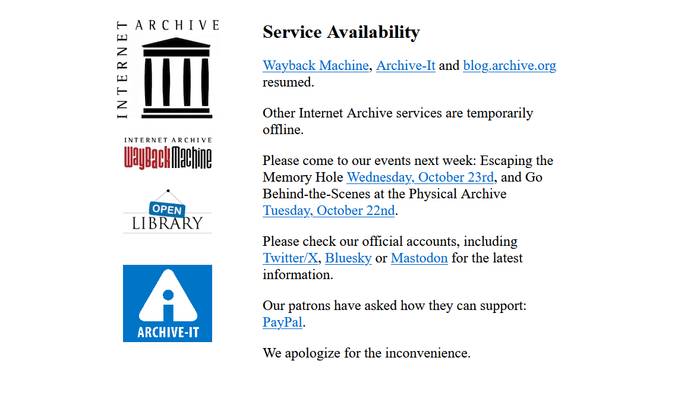

At the time of writing this post, even though the Archive has been reportedly restored in a read-only manner, some of its main features still have connection timeouts, meaning they are still having some unresolved outages.

Worse still, it’s been reported that some of its content has been erased, although we still don’t know the scope of the damages.

Being one of the largest digital libraries in existence, its recent history has been a close parallel to the Great Library of Alexandria, with this event being probably the counterpart of the fire that burnt a large part of the library, although not completely.

Hopefully, it will soon be restored and remain relevant for years to come. Still, this should serve as a lesson for the future to prevent history from repeating.

Internet Archive has seen better days. Last month, they lost a case against Hachette Book Group (and others) that was around since May of last year. The printing companies alleged that Internet Archive was allowing people to infringe copyright when they lifted borrowing restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic, and will have to pay several millions of dollars in damages, maybe up to $400 million.

And on May of this year, they were the target of another DoS attack, albeit to a much lesser degree than this one. While I’m not well informed in digital security to discuss about how they got hacked and if the security measures they had in place were good enough or not, the fact that this has been going on for nearly a month now goes to show that the hackers are not planning on stopping for the time being.

Now, I’d generally wait a few days when events like these occur to write my opinions about this matter as we get more information on who is responsible for these hacks and under what motivations, but this event seems like it’s going to take quite a bit longer before things return to full normality.

But seeing as certain parts of the site have been tentatively brought back online, I thought it would be a good time to talk about some insights on this.

Still, I would heed caution when hearing news about this, at least until all Internet Archive services return back to normal and they’re done investigating the causes and finished making an assessment of the damages. I’ve found a lot of misinformation about the topic; which is y’know, the usual in developing big stories.

The Internet Archive is mostly known for its WayBack Machine, a comprehensive archive of over 866 billion webpages since 1996, and while to some people it’s just a way to reminisce how websites used to look like in the past, it does have its usage as a very valuable resource for legitimate use cases such as documenting about legacy software, or retrieving data that no longer exists in the present —sort of like a preventive solution to link rot.

However, archive.org also has a repository of many types of media, mostly digitized books, but also music, movies and software. This is also part of the rationale behind the debate of copyright infringement, as the borrowing system is only applicable to books. Still, the Internet Archive does accept takedown of personal data if someone wishes it rather not appear in the archive.

I have relied on this archival service for many years and I even contributed to it a few times. It’s such a pleasure that it’s a non-profit organization, so everything there is free to the public.

My take on this is that attacking a public project of this scale equates to a crime against humanity itself. Let me explain why with a bit of history.

The concept of a digital archive represents our most recent level of advancements in storing knowledge. Throughout history, texts had been etched and written onto many kinds of surfaces. Some are durable, while others are reusable, but all of them are subject to being defaced, altered, or destroyed by both natural and humane causes because they are physical objects.

Plus, before the printing press was invented, scribes had to be employed to make copies of documents of any kind and medium, and were very predominant in many cultures from all parts of the world. There’s even a branch of science that studies how writing systems have contributed in shaping other aspects of culture, among other things.

The ability of representing knowledge using concepts such as numbers like 0s and 1s allows people to store it in a more abstract way, protecting them from most of the natural causes. And as it turns out, computers turn out to be very good at copying information flawlessly. In order words, digital information grants people with the ability to share knowledge easier than ever before.

However, knowledge still is —and will always be— susceptible to human damages. And we’ve seen this with attacks and boycotts to libraries and museums alike. Not even the digital repositories are safe from this.

And this is where the similarities between the incidents of the Internet Archive and the Library of Alexandria start to run out. To provide some historic context, the Ptolemaic library wasn’t destroyed by the infamous fire. In fact, the Museion, a somewhat independent institution but in which the library belonged to, still remained active centuries later. Historians still argue about several contradicting details, but what’s clear to most historians is that it didn’t disappear all of a sudden, rather, the library had a slower and steady decline.

The Library of Alexandria wasn’t the only large library of its time, either. The Library of Pergamum was claimed to have over 200 thousand volumes, and it has been rumored that Mark Anthony offered the entire collection to Cleopatra to restock the library, damaged by the fire 5 years prior. And its decline was not that much of a big deal anyway, as historians believe that most of the material within the library actually survived the demise, thanks not to other cultural centers such as the Library of Baghdad, but the many copies of the stored scrolls made by scribes over the centuries.

The Internet Archive, however, is probably the only archive of its kind when it comes to “archiving web pages in their entirety”, holding nearly 100 petabytes of data as of September 2024, and many other archiving initiatives are backed by their technology. In other words, it’s a centralized source of information.

As a matter of fact, Google was using their own infrastructure to cache pages when they couldn’t reliably load due to server outages and the like. But as of last month, they have removed this feature and integrated their cache functionality with WayBack Machine instead.

A bit funny considering it happened right before the attacks.

This is why these attacks are actually a much bigger deal than other historic examples: We’re dealing with a totally new form of knowledge, one that we’re still figuring out how to effectively archive, despite modern advancements; I don’t know about any examples of “digital copyists” of old websites, for that matter. And there’s a lot in that archive, so if an outage and data loss does occur, it must rely on volunteers who have kept their own personal copies to restore it. Sure, we have a lot of people in this planet, but lost media is still a thing.

Regardless of their intentions and motives, it should be taken as fact that these hackers have proven that the current model of archiving the web is far from being “permanent”, and it can easily be brought down by factors such as hackers, or maybe even lack of funding (some historians argue that’s what brought the Alexandrian Library to its final demise). If we want to truly keep it that way, I believe we should try to decentralize our archives more, just like scribes used to do by copying tablets, scrolls and books in the past. Of course, this would imply a lot of backup copies and maybe even using decentralized networks such as IPFS, which will anger copyright holders, but further defining fair use and hopefully some court rulings in favor for archival could help in making this feat much easier to do.

Every man has two deaths, when he is buried in the ground and the last time someone says his name. In some ways men can be immortal. — Ernest Hemingway